Ramblings: December 2023

14 January 2024

Below are collected Twitter/X ramblings for the month of December 2023. As usual, I’ve got more commentary on the themes of the month below the original posts.

This month’s photo of the month is a vista from the Mattabesett Trail in Giuffrida Park, Meriden, CT. This loop over Chauncey Peak and Mt. Lamentation affords some of the best view/effort ratios for hiking in Connecticut. It’s beautiful in any season.

The number of new and creative predation methods that land in my inbox these days beggars belief. Most of these offers to sell conference attendee info are not legitimate, but it’s also true that many societies do sell attendee info to marketers. I’m not a fan of that since: 1) industry attendees are already being shaken down by the conference organizers with the highest registration rates, which they know deep-pocketed companies will pay; 2) the amount of cold call business industry attendees are going to do this way is close to zero; and 3) I’m not the right person to reach out to for that kind of stuff anyway. So: delete and move on to the next email.

Oof, this story of a botched phase 3 clinical trial was unfortunate. Getting to a phase 3 trial in the first place is hard enough without having your randomization messed up. That’s the king of unforced errors. Thankfully, it seems like in this case that patients weren’t given doses that could’ve brought them to harm. But you can easily envision scenarios where the next company to make this kind of error might not be so lucky.

I’ve railed at length about the over-reliance of new degrader papers on BRD4 as the test case. BRD4 is almost uniquely predisposed to be degraded, and therefore it doesn’t stretch a new approach to its limits. It’s the easiest, most cautious of cases, with limited power to convince me (or anyone else) that a new approach is broad, general, or capable of handling tough cases that are orthogonal to existing degrader approaches. Take this lovely example which showed that KEAP1-recruiting degraders seem pretty limited in their scope. Sure, they can take out BRD4, but they also fail to take out targets that are easily tackled by CRBN et al.

I don’t have quite the beef with Elon Musk that many other SciTwitter folks do, but there are things like this that annoy the shit out of me. The dude is so obsessed with making Twitter/X the only place where users rest their eyeballs that their algorithm now punishes posts that contain links to outside sources. Like, say, the entire universe of scientific publications. That’s so at odds with the way scientists think and work, and there’s no solution for it. This component of the algorithm sucks.

Chances are, if it’s being done right, it’s not being done by George Santos. Don’t be like George — embrace the free drug hypothesis.

This home explosion in Arlington, Virginia made the rounds on social media back in December. I couldn’t help but think of an impact testing gone wrong in a home lab. Sometimes I think the process chemists went into process chemistry just so they could try to blow stuff up on purpose.

This all goes together, and crystallizes a lot of my thinking on how the AI crowd is charging into drug discovery with a tech bro attitude. The heart of the argument here is my suspicion that the biology of anything is not a fundamentally reducible system like a semiconductor chip. Biology wasn’t designed; it evolved. Interactions within a single cell, between cells, between organs, between organisms, and with the surroundings are chaotic and not fully predictable by a model. It’s possible we’ll build crude models that are good enough for us to start tackling some diseases, but this is going to be an uphill, generation(s)-long slog. I think too many of the AI crew feel like this problem just needs more reduction and a shit ton of compute power, and with that alone they’re going to come in and blow all the folks who have been doing drug discovery for decades out of the water. That’s their own biases from their own fields working against them, and many rude awakenings lie ahead.

The Bayh-Dole act entered the news in December when the Biden administration announced they were going to start pushing to enforce march-in rights. This is a complex topic that Derek Lowe delved into very nicely, but I’ll just hit on a couple of things here.

First, there’s the issue of the invention needing to be (in part) funded by a federal agency. This is the point I pressed on in the Twitter thread above. Having a good idea for a target is important, and having a tool compound to interrogate the target with is also important. The crux of the matter is: if a government lab, or an academic lab with federal funding, does those things, is that “invention”? In my non-lawyer-but-nonetheless-informed-by-20+-years-of-doing-this opinion, unless the tool compound becomes the clinical candidate, and eventual drug, the answer is clear: no. More often, a pharmaceutical company may take that foundation of knowledge and then go on an often-years-long campaign to discover new, better chemical matter that has the chops to be a drug candidate. The non-triviality (non-obviousness, if you prefer the legal standard) of that process is the entire reason that I and thousands of comrades-in-arms have jobs. It’s not just a simple reduction to practice now that the target ID work has been done — indeed, if it were just reduction to practice, that would not meet the legal standard for a patentable invention. When patents are filed, it’s that chemical matter that is protected. Patents cover composition of matter — the chemical structures themselves, and the chemical structure of the clinical candidate more specifically. They do not cover targets or (generally) tool compounds. Does the foundation of knowledge provided by the lab that identified the target and the tool compound constitute part of the invention? Legally, to my understanding, no.

A second part of this discussion is that march-in rights need to be applied in the context of the federally-funded invention not meeting “requirements for public use” — and in the Biden administration’s reasoning, part of that test is based on drug pricing. That’s a controversial take for sure, but getting beyond the scope of what I want to talk about here. I suspect that any such actions based on that interpretation of the law will be subject to years of vigorous legal action.

Putting together the federal funding requirement for march-in intervention with a fuzzy interpretation of the provisions to include pricing as part of the public use standard, I’m unconvinced that this is the right way to achieve the desired goal of broadly reducing drug prices. The circumstances under which these provisions might apply seem so narrow to me that this sounds more like putting up the appearance of doing something about pricing rather than actually doing something about pricing.

Drug pricing in the US is surely a mess. But it’s driven by a complicated web of interactions between the manufacturers, distributors, insurance companies, the government, pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers, and more. I, just as much as anyone else, would like to see fair and affordable drug prices set through a transparent process. We don’t have that process today. As much as I admire the spirit of what the Biden administration is trying to achieve through enforcement of an existing law, which avoids the need for messy Congressional intervention, I sense it’s mostly shouting into the wind. The real reforms that will move the needle here are hard, doubly so because the US government borders on non-functional these days.

I’ve seen many projects over the years turn into shambling zombies because of this phenomenon. A series of modest tool compounds is made and tested — and the data is vague. Low micromolar binders with a whisper of SAR. So you try to build another assay to confirm the activity, make a few more compounds to expand the SAR and drive potency down into the nanomolar range, and what do you get? More ambiguity, a few more months lost — and no closer to the goal. Lather, rinse, and repeat. Ongoing ambiguity is, by itself, a red flag, and should be invoked more often as a reason to stop a project or chemical series.

I’ve seen projects go astray many times because the team doesn’t understand what the assay is and isn’t telling them. In the long run, it’s almost always worth the effort to build the most physiologically relevant assay(s) that you can, even if they’re lower throughput or more costly. They can always be put in a screening cascade downstream of a higher throughput assay for benchmarking. And they thus provide a good cross-check of that higher throughput assay.

Gremlins and Poltergeist are two movies that GenX parents probably shouldn’t have let their kids see at such a young age, but here we are, emotional scars and all.

I’ve made progress on this write-up over the last month, with some help. Expect this now-collaborative project to publish fairly soon!

There’s research out there on the right ratio of praise-to-criticism, and it’s something like 5:1. My experience is that scientists often tend to take the success of their teams for granted, and laser focus on the things that need to be improved. While that naturally falls out of the mindset of optimization (we don’t call it “lead optimization” for nothing!), it’s also not what motivates people. Take the time to celebrate everyone’s successes, even small day-to-day things.

As I’ve moved up the management ladder, more of my time gets consumed with administrative things and managing people and portfolios. I still have time to do real drug discovery science, but it tends to be an hour or two here or there that gets fit in around my other responsibilities. A full day of this time without interruption is a glorious and rare luxury.

A lot of disciplines have a clear connection between how folks are trained in grad school and the eventual work they’ll be doing in industry. Medicinal chemistry is one of those few where the majority of learning the discipline is done on the job. We tend to hire people who have the raw materials of organic structure and synthesis at their disposal, and then use that as a foundation on which we’ll build the rest. This perhaps makes it a little easier to break into industry than some other disciplines, because the apprenticeship path is well-trodden.

I’m still noodling on how to put all of this together in a single framework and haven’t started writing anything in earnest. I also have a number of other writing projects, including the aforementioned layoff survival guide, that I’m trying to finish first. But I’ll get to this eventually!

Parental leave, including for new dads, has come a long way since my kids were born. I didn’t think much about it at the time — it’s just the way employment worked in the US. It wasn’t much better for new mothers. Six weeks of short-term disability for a vaginal delivery and eight weeks for a C-section was normal. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) extended that to 10 weeks, but it ran concurrent with your short-term disability — and when disability ran out, the remaining FMLA leave was unpaid. The half year (or more) chunks that my European counterparts got — including dads — seemed an unimaginable luxury. The US still has some way to go to meet that European standard, and it’s still applied unevenly across US pharma companies, but there’s been progress in the last 10 years. I hope it continues.

With careful planning, there’s no need for a student on a budget to spend a nickel on dinner at a large scientific meeting. Many working group sections have dinners and symposia in the evenings. You can show up to many of these legitimately if you have interest in the subject matter. But I’m not above a little irreverence when it comes to these presidential-type receptions. If you need to crash a reception at a scientific meeting, I’m your guy.

The broad strokes are right, but the details are, of course, horribly wrong. I wouldn’t mind the glass of whiskey on my desk though.

I cross-posted this on LinkedIn, and it actually got more traffic over there than it did on Twitter. Who knew?

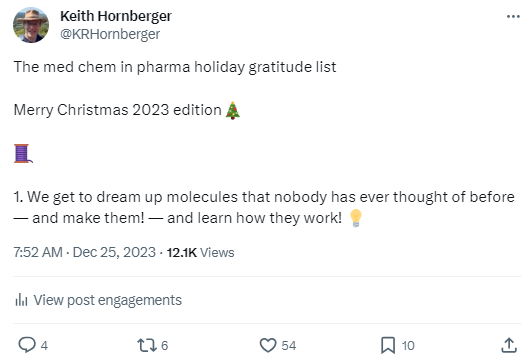

I think it’s important to periodically count one’s blessings — at work and otherwise. I consider myself fortunate to have a job that I love that pays well and has tangible benefit on human health. Sometimes we lose sight of these things in the fray of the day-to-day.

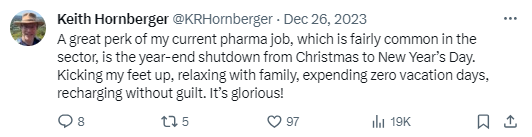

Every employer I’ve worked for has either had a year-end shutdown or offered more paid time off than standard in the US so that you could easily take this week off without impacting other vacation plans for the year. It’s a far cry from my grad school days when I’d head home to visit my parents on the train on ~December 23, and then return to school to keep working in the lab on December 26. I think it’s a great cultural move for a company to have a shared week off at some point during the year. It’s then understood that everyone is idled, and there are no expectations other than to relax and enjoy that week as you see fit. The only emails I got during my week off at the end of 2023 were from people outside the company — who presumably didn’t have the same luxury of a week off.

I’m glad that this series on pharma interviews and hiring was popular and helpful to folks. I also wish that people would make their likes public instead of using bookmarks. And I also encourage people to retweet resources like this that were useful to them so that more people can see the same resources. A lot of what I write is me paying forward any number of lessons that I had to learn the hard way. Help spreading the word is the best way to say thanks.

The amount of stuff that’s allowed to slide into the med chem and chemical biology literature is staggering. As a reviewer, I do my level best to hold the line. I try to find the good things in everything I’m asked to review, and seek to help the authors find a path to publication in all but the most egregious cases — but I’m also not going to be shy about calling out where there are data deficits that make sweeping conclusions hard to justify. The literature would be in much better shape if folks simply acknowledged the limits of their data sets and stopped trying to reach beyond the data’s grasp in an attempt to make a splash.

Industrial scientists generally don’t publish as often as their academic counterparts. Publication isn’t our goal — discovering drugs is. I’ve said before that patents are the coin of the realm, and that’s where our first priority has to lie. On those infrequent occasions when we get to put a chunk of our work out in the public domain, we stop to celebrate. I’m proud of this piece of work and glad we got to share it with the world.