Below are collected Twitter ramblings for February 2023, with the usual dollop of color commentary mixed in.

This month’s photo of the month was taken at Macricostas Preserve in New Preston, CT. Litchfield County is in the foothills of the Berkshire Mountains and has some of the best hiking in the state.

C&EN was the last decent benefit of ACS membership for me, and at the beginning of February, ACS leadership appeared hell-bent on destroying it. The move from Publications to Communications, all the nonsense about being the “organ of the ACS”, and the staff firings and resignations seemed on an irreversible trajectory. As someone who’s been in oncology research for most of my professional career, I rarely go to ACS National Meetings anymore — our premier venue is the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting. So it was the magazine or bust. I was astonished at the rapid reversal that came a month later.

I’m sometimes asked if I’d ever consider writing a book about medicinal chemistry. I’m not sure I could. For one, it would have to be in my breezy, snarky style — and while there might be an audience for that kind of thing, whether or not there’d be a publisher is a different question. For another, I can’t begin to fathom how I’d tackle ligand-receptor interactions, structure-based drug design, and the like. Modern medicinal chemistry pedagogy is overweighted on this stuff, and my thinking is out of sync with that thinking. I’d include a single chapter on ligand-receptor interactions, under duress. Go back and read my tweetorials: how many of them are about ligand-receptor interactions? (Answer: none — because the very problem bores me to sleep.) What we really need to talk about is the meat of pharmacology, which is in vivo: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, efficacy, and the relationships between those things. Also all the attendant ADME concerns. And above all that, the delicate balancing act, the trading off of one thing against another needed to deliver a drug candidate.

This series on the nuts-and-bolts details of transitioning from academia to industry has been well-received so far, so I’ll keep doing it. Some of these things seem obvious in hindsight. When I think back to my own first go-round of interviews coming out of grad school, though, it strikes me that academia could do a much better job arming folks with this information.

Most compounds in discovery will die, and quickly. It’s rarely worth the time and effort of medicinal chemists to maximize yield, because the real goal is to test the compound, (likely) kill it off, and move on to the next thing. This gets us all manner of grief from both academics and process chemists (an unholy alliance if ever there was one!), but it reflects the practicalities of what we have to do. When we find an interesting compound that needs to be scaled up, that will trigger increased investment in the synthesis as yields become more crucial on scale.

Sole hike in the month of February. Macricostas is an old reliable for me. The overlook and summit views are much better in the winter, and the preserve is quieter too. It was a special treat on this one to hike a brand new trail that just opened in the last few months. The new trail wasn’t especially challenging, but it was fun to do something new at a place I’ve been to many times.

The simple joys and lack of encumbrances of childhood would serve us scientists well in our creative process. We lose all of that somewhere along the way. Stay curious.

I’ve also heard another tale (maybe apocryphal) that after dabrafenib (Tafinlar) hit the market, the CEO of GSK had a town hall and wanted folks on the discovery team to stand up and be recognized. Nobody stood, because they had all been fired, and the CEO had no clue. Sometimes big companies can be incredibly stupid in their human resourcing decisions for inane business reasons. It’s not that complicated: figure out who in the organization is delivering assets and value. Keep them at all costs. Bend the organization around them.

I guess this is the price of having like 50 people left running Twitter. (I exaggerate, but this kind of goofiness seems like it’s not going to go away.)

Laugh and shake your head is all you can do on a lot of days in drug discovery. It can be a sausage grinder, a shore where all your dreams go to get dashed. In my experience, progress on discovery projects is rarely linear. There can be long stretches where things are just stuck and not advancing at all, and you question your desire to be in this line of work. Then something cracks open and a torrent of progress comes very quickly. When those times come, you put your foot on the gas all the way to the floor and drive it for as long as you can — because those times never last. The next plateau will come and stagnation will resume. Persevere on a project long enough to string together a few of those big breaks and you just might get a clinical candidate.

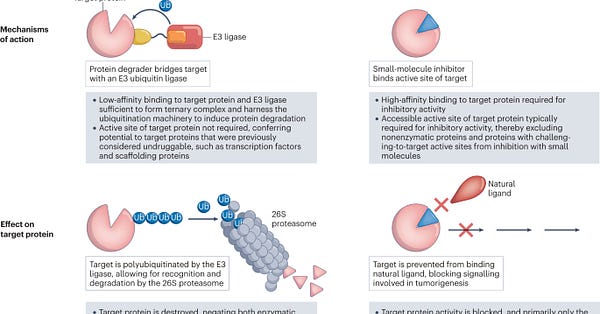

I enjoyed putting this review together with Debbie and Craig. It’s a compact summary of where we are with heterobifunctional degraders and then a close look at how things are going in the clinic. Much of the clinical data has only been released at conferences and it’s hard to get your head around it all sometimes, so I hope this review has done some good for that.

This was quite the sight, and even my teenagers were mesmerized by ~60 dots tracking in a straight line across the sky. Of course, the satellites spread out more and lose their naked eye visibility as they raise to higher orbits, but it was still interesting to see some real space tech in action.

Until the day comes when AI can attack clinical trial failures head-on (with the noisy and incomplete data sets available there): tool in the toolbox, and that’s it. Beware of Skynet’s handlers bearing gifts.

I was born and raised in Maryland, and seafood (especially blue crabs) are central to that experience. Old Bay shakers are optional.

There’s a good career point in here. Over the years, I’ve done data pipelining in KNIME, spent a lot of time helping to manage the research informatics infrastructure, built tools for human dose prediction — and a host of other things. Math and logic skills were the gateway to all of those things. They opened doors for me to learn new things while also benefiting the company I was working for. If you have skills that are maybe not strictly required for a role, but they’re skills you enjoy flexing — then keep flexing them. Don’t suppress something you’re passionate about just because the job doesn’t require it. Find a way to make it part of the job instead. You’ll be happier in the long run.

The academia-to-industry career transition series is the main thing right now. So many things to demystify. I’ll keep doing it as long as the interest is there.

And speaking of, here’s the next installment in that series, this one on site interviews. Still some more things to say re: negotiating job offers, handling when you don’t get an offer (or any offers), the “first day on the job” experience, etc. Stay tuned!

Ah Joel. We medicinal chemists know how you feel sometimes.

Why we decided it would be less work to let the kiddo have his birthday party at home is still something of a mystery to me.

Complete 180 by ACS in the space of a month. C&EN moved back to Publications where it belongs, no more “official organ” BS. Unfortunately this self-inflicted wound has left their staff gutted, and it’s gonna be a huge lift to re-staff. The experience lost will take a long time to replace. I hope they pull it off.

Seriously, don’t do this. Sweeping conclusions from small studies are either ego stroking and/or ignorance of the implications of what you’re saying. Neither is a good look.