Ramblings: February 2024

31 March 2024

Below are collected Twitter ramblings for February 2024, with the usual expanded commentary throughout.

This month’s photo of the month is from an overlook on the Ives Trail in Danbury, Connecticut. There are still a lot of gray days in Connecticut at this time of year, but the flip side is the trails were quiet.

Much ink has been spilled about the notion of work-life balance, but a lot comes down to how it’s hard or impossible to find. Although I don’t work in academia, many of the comments I’ve read are from people who do and are working themselves to the point of burnout. Relationships at home suffer. People forget to take care of themselves physically and emotionally. I can at least confirm that my own time as a graduate student was pretty intensive, and working 60+ hour weeks was normal. I note in fairness to my advisor that he didn’t expect folks to work this hard, but everyone did anyway — peer pressure from the hardcore folks often squeezed everyone else into conforming.

There’s a temptation to view industry as a panacea that gets one away from this overwork mindset, but I think that reality is a little more nuanced. While it’s true that there will be less peer pressure overall to work ridiculous hours, we are not exempt from occasionally needing to put some extra time in. Out in the real world of drug discovery, there are sometimes immutable deadlines. A big one for the medicinal chemists is patents. When we file a provisional patent application, there’s a period of a year after filing to make updates and changes before it converts to a non-provisional filing, which can no longer be changed and will publish six months later for the world to see. When a non-provisional conversion deadline is approaching, it’s your last chance to add useful compounds and data to the application. You can bet that the weeks leading up to such a filing can be pretty intense, because if you miss the boat, that’s it — you missed the boat. Process chemists can also talk to you at length about the realities of batch deliveries in the plant.

The important word in the last paragraph is “occasionally” — while we do have bursts where we have to put in extra time to get things done, it should not be the norm in most industrial chemistry settings. If it is, that’s a sign that a workplace may not have the staff that it needs to execute the company’s mission — or that it has an unhealthy culture where routine overwork has been normalized.

In my current job, and most (but not all) of my previous jobs, I feel like I’ve been able to balance my time between work and home. Plenty of weeks are close to 40 hour workweeks, and I’m home to see my wife and kids and go hiking on the weekends and go to see my oldest son perform in the spring musical at the high school and be a den leader for my youngest son’s Cub Scout pack and go out to dinner with my wife and go to the movies and read books and watch TV and make a fancy dinner at home and… you get the idea. In my first industry job, I spent a couple years grinding it pretty hard because I had a mindset hangover from academia and felt like I had something to prove. There were lots of nights where I’d stay at work till 7 pm or later, and there were tumbleweeds in the hallway because I was the only one still there. In hindsight, that said more about me than the company.

Attitude matters a lot. The flip side of work-life balance is that work can become a 9-to-5 clock-punching exercise, and is that really how you want to spend your working life? I don’t know a drug discovery scientist alive who’s effective in their job while not giving it their all — because they want to — during the time they’re at work. Biotech is built by true believers and they want to attract and retain people who feel the same. Care. Give a shit and work your ass off while you’re there. And then go home and live your life and let it go until tomorrow.

The layoff survival guide was a year in the making. I had about half of it written and got some good feedback from Chemjobber that encouraged me to keep going. But… it was a big project and I got sidetracked chasing shiny objects instead of finishing. Fortunately it came up in Twitter conversation at the beginning of this year, which is how Vega Shah came on board as a coauthor and helped me get this project across the finish line. (Thanks Vega!) I have the utmost respect for writers who have the discipline to sit down and just pound out a few thousand words every day. My own writing tends to be in fits and starts. For example, I’m writing most of the words in this whole blog post in a single sitting rather than steadily banging away at it over a week or two.

I suspect that a lot of the guide’s content, while written with the pharma & biotech sector in mind, is more broadly applicable to layoffs in other sectors. The underlying law is the same in the United States, and I sense many categories of knowledge worker (IT, engineering, etc.) will have similar experiences. The guide is something I’ve had in mind for years, because when I was laid off relatively early in my career, I was totally unprepared for it. Once I got back on my feet, I vowed that someday I’d write something so that others didn’t have to learn things the hard way. (Actually, a lot of my writing stems from this notion in general!) While I hope that nobody ever has to go through a layoff, the reality is that these days, most or all of us will eventually. So the resource is here when you need it.

I get dozens of DMs a week, and most of them are from complete strangers. While I want to be as helpful as I can be, there’s only so many hours in the day — see that post above about work-life balance. I’ve also had some experiences where people make a seemingly simple inquiry, and when I do respond, they then want to go down a rabbit hole of asking for super-detailed career and educational advice, and I’m like — whoa! I’m flattered that a total stranger would trust me to give them career advice. But if I responded in detail to all of these requests, I’d probably have to stop sleeping to make time. So unfortunately, the advice I give will largely have to remain at the generic level of a Twitter post or blog post. I do encourage everyone to find someone in their life though who can be a career mentor. We all need that kind of guidance sometimes. There are people who I do currently mentor both formally and informally in a more detailed way, but I’m out of capacity for much more. Sorry!

I’ve written extensively before about the risks of polypharmacology with compounds that are micromolar engagers of their putative primary target, and that’s compounded when the maximal response is shallow even at those whopping concentrations. I’m at the point where I’m out of time for such publications, because so few of them are going to check out in the long run. One of the first scans I make in a med chem paper is for what concentrations the tool compounds are tested at. If it’s well into the micromolar range, I stop reading right there. The follow-up publications from the same labs where they then find nanomolar compounds against the same targets somewhere down the road are almost nonexistent. That could be because they’re not sufficiently incentivized to find such compounds. But more often it’s because the original compounds were, quite frankly, bullshit — and there was nowhere else to go.

But hey, at least nobody reads those papers, which use micromolar compound X to draw strong conclusion Y about target Z. And then conclusion Y doesn’t get repeated as gospel in the literature forever afterward. Oh, wait.

It’s important to separate performance management from its documentation. Performance management happens in the normal ebb and flow of conversation between a manager and their direct report. It’s all the encouragement and reinforcing when something was done well, when a problem was correctly anticipated, when good judgment was exercised in the face of a complex situation. And also constructively showing a better path forward on the occasions when those things don’t happen. And delivering it all in a way that builds the relationship between manager and report. Even when I have to deliver negative feedback to one of my reports, I try to do it in a way that they know I’m in their corner and am telling them what I am to help them get better in the future. I want all my folks to unlock their best selves. There’s nothing more gratifying as a manager than when someone in my group “gets it” on a new skill set and spreads their wings. It’s glorious to behold!

Those performance management forms? Remember where they’re coming from: human resources. Those folks do have a job to do, and among them is to protect the company when there are personnel issues. There’s good reasons for a written record of performance to exist, and we all have to acknowledge and work with that. So fill them out because you must, but also center that they’re not a vehicle or substitute for real performance management.

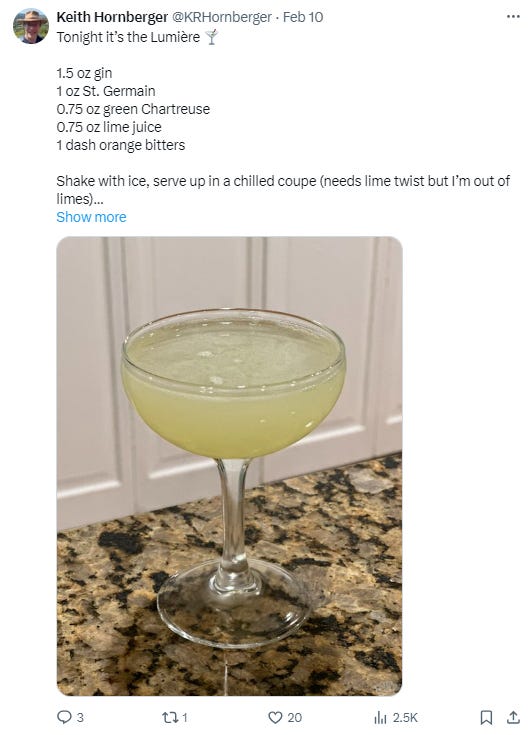

Rarely do I add a new cocktail to the repertoire that’s such a hit that it becomes part of the regular rotation, but such is the Lumière. It has a lively herbaceous quality from both the gin and the Chartreuse that’s perfectly balanced by the elderflower sweetness of St. Germain and the acidity of lime. Perfect for any time of the year!

It must be nice to have independent means and be a professor without actually getting paid. Can you imagine that model anywhere in the world today? Pay in academia is already a notoriously sore subject in many corners, especially for adjuncts.

I get dozens of these predatory journal requests a week, and it’s just delete, delete, delete on all of them. When they say “valuable manuscript submission” it’s almost like they’re saying the quiet part out loud: it’s valuable to them as the publisher because you’ll pay them publication fees and then they’ll charge subscription fees for others to read it. It doesn’t even need to be real results or any good — as long as you pay, it’s valuable to someone!

I like Peeps, and I like Dr. Pepper. But I just can’t get behind this mashup. 🤢

This started when someone posted something awful about basically needing to have your professional career path laid out when you’re a zygote or something. Yeah, so. Reality is just a tad bit messier than that for most people. Learn. Find things that you’re interested in, learn more. Passionate about it? Learn more, maybe you can turn it into a career. Even when you do, it won’t be exactly what you expected, so you’ll have to learn even more. And maybe that will send you rocketing off in an entirely different career direction. The best scientists — no, the best people — I know are the ones who make a commitment to lifelong learning. They know lots about lots of things. They may specialize in one thing, but are also prone to going in a totally different direction if their interests change with time. I strongly feel we’re not meant to be just one thing in our lifetimes.

So here we come at last to the retat stemm cells and the rat with a four-testicled giant penis (or dissilced, if you prefer) — thanks so much, AI-generated figures in sham research article. This mess was promptly and correctly retracted, but it never should’ve been published in the first place. I worry very much that as AI gets better at image generation and writing text that this is going to be no laughing matter. It may not be so easy to separate truth from fiction in another generation, and opportunists who care about profit more than truth are going to capitalize on that. We should all be concerned.

Real talk: I was something of a competitive loner when I first came to industry. I think a lot of people who came out of total synthesis groups 20+ years ago were this way too. It was a mistake spending time trying to make myself stand out from the crowd, when in reality the time would’ve been better spent learning how to operate in a team environment and build relationships to get things done. When you learn the ropes and good discipline and decision-making, the rest will start to follow on its own. I shrugged off that competitive coil eventually, but my graduate training had definitely left me at a deficit at the beginning of my industrial career. It’s way more fun now to watch the team succeed, and to root for everyone else’s success. The best teams lift each other up.

I originally posted this like a year ago with little fanfare, but a few posts busting on Jensen Huang later, now it did some numbers. Although the joke is at the expense of AI ligand discovery here, the same logic can be applied to any new research technology. The inescapable question that all new technology needs to answer for is: how is this tech going to improve the odds in clinical trials? Only breaking through on this rate-determining step is going to have a hope of improving the overall cost and efficiency of the drug discovery process. The answer doesn’t need to be complex: it might just be that the tech allows you to access a great target that wasn’t previously accessible, or in a more comprehensive way. But there needs to be an answer to this question, or you’re just spinning your wheels on the wrong problem.

I don’t know why this has been a thing on Twitter for years, but it has been. Let’s instead all just acknowledge that anyone who’s earned an advanced degree has earned the right to use the associated honorific as they see fit, and leave it at that. Every degree program has its things that it emphasizes and makes one a specialist in. And no, just because your speciality is the functioning, maintenance, and repair of the human body does not make you special-er than anyone else who, say, helps to discover the drugs that you’re prescribing. Peace not war — we all add value to society.

The replies on this post were interesting, because there can be several stages at which a rejection can happen. When I originally posted this, I was thinking primarily of being rejected after you’d already progressed to a site interview — or even a phone interview. In those cases, I think it’s rare to not get some kind of notification that you weren’t selected or aren’t progressing further. But at the stage of an application only, then yeah, it seems like the common experience is to just be ghosted. Initial resumé triage is done quickly. There might be hundreds of candidates for a posted position, and you might phone interview only 10 of them to bring 2-3 in for a full interview. So I get in that initial rush why there may not be a personalized letter sent out to everyone who may not have made the initial cut. But at the same time, c’mon. It seems like common courtesy to me to let people off the hook so they’re not just sitting around waiting for Godot — even if it’s just with a form letter, give people some closure.

They call it a reproducibility crisis for a reason. Those initial results in the literature fail to check out far, far more often than they pass muster on closer scrutiny. We can argue about the reasons for this, but as a biotech scientist, I only care about the end state. We cannot start and run a project built on a foundation of shoddy preliminary science. The clinic is a harsh mistress, and she gives zero f&*ks about how brilliant you think your last Nature paper was. If we test the ideas out in our own hands — and we always do, because we can’t afford not to — and they don’t stand up, then it’s on to the next thing. Far better to fail these ideas out early than get years down the road — and maybe hundreds of millions of dollars of cost sunk — and find out it’s not quite the way you thought it was. We have a hard enough time (to the tune of 90-95% failure) getting through clinical trials even when we’re working on the things we think truly have a shot.