Below are collected Twitter ramblings for June 2023, with the usual additional commentary interspersed.

This month’s photo of the month was taken on the Appalachian Trail near the summit of Race Mountain in Suffield, Massachusetts. Spectacular views and relatively accessible to those with moderate hiking ability, at least as these things go on the AT.

I think this was Thai food? Anyway, the Yale food trucks are one of the best meal bargains in New Haven and they’re conveniently walking distance from my office. Hard to find another locale where you can pack in quite as much food for the price.

A great deal has been written about chemical probes and their (mis)application over the years. Unfortunately, it seems that even when folks identify and qualify high quality chemical probes, they are still prone to abuse in other labs. This paper does a good job calling out egregious probe misuse, including using them at very high concentrations and not including negative controls. If there was a single thing I wish I could instill into folks about using chemical probes, it’s that use of high probe concentrations — let’s be generous and say 10 uM or above, although even 1 uM starts to sound the alarms in my head — is almost always a pharmacology red flag. Especially so when the intended target is adequately covered by the probe at a concentration that may be orders of magnitude lower. Even the best probe compounds will start picking up off targets if you apply too high of a concentration. Maybe put another way, folks are too willing to believe the myth of specificity, which is always concentration dependent and breaks down in the extreme. The “more is better” school of pharmacology often rules the day in the literature, and it’s so often down to a simple lack of critical thinking. Does this probe concentration make sense? What are the risks I’m incurring at this concentration?

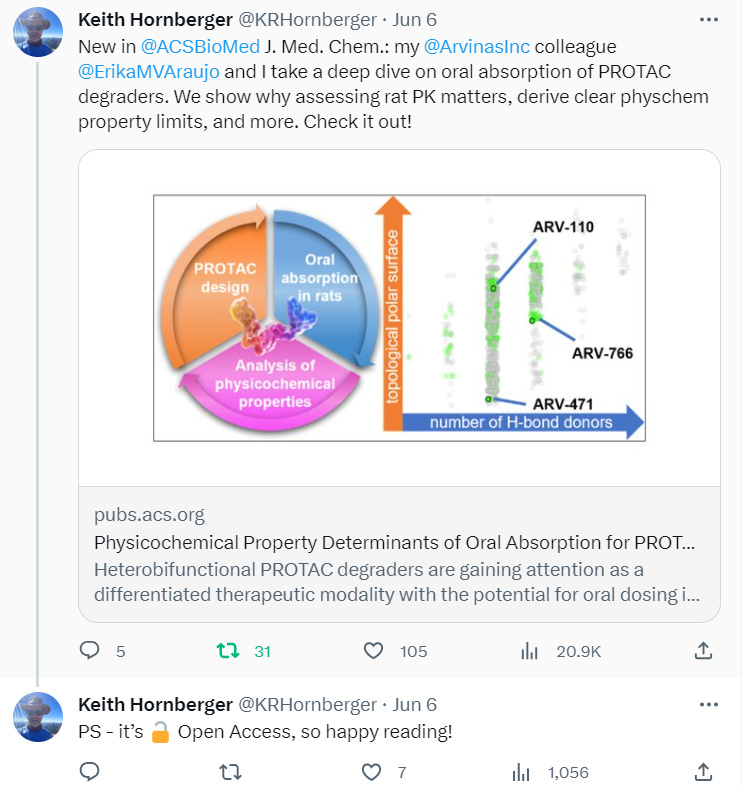

I’m thrilled to have finally published this paper, which I encourage anyone working on heterobifunctionals to give a read. It’s open access too, so no paywalls!

While I’m a proponent of emphasizing your transferable skills, and I also understand the desire to not pigeonhole yourself too much, at some point there are specifics that matter. If I’m hiring a medicinal chemist, some basic qualifications are likely to include a PhD in synthetic organic or medicinal chemistry, or a BS/MS in the same with lots of practical experience in pharma. Yes, I care about your enthusiasm and problem solving skills too, but not at the expense of basic educational qualifications for the job. There’s a happy medium of emphasizing your transferable skills without obfuscating certain basic educational credentials or work history.

Some of the things I saw that people were willing to do, like parting with digits or whole extremities were, well, a little extreme. This culture, even in jest, is unhealthy. I’ve never published a paper in Nature or Science, and I doubt I ever will. Does that diminish my accomplishments as a scientist? Am I losing sleep over that at night? If you think the answer to those questions is yes, it’s maybe time to reevaluate some life priorities.

This is a good idea and I stand by it. Or maybe make it a mandatory field to fill out during the journal submission, and a 10x disconnect is an automatic desk reject without a damn good explanation. There could even be an optional text field to fill out during submission called Damn Good Explanation.

This hits directly on a lot of my AI misgivings. AI is indeed a useful tool, especially for ligand discovery, but there is way too much conflation of ligand discovery with drug discovery. Let’s separate the hype from reality. AI may one day get to a place where it can routinely positively impact clinical trials, but that day is not today. Nor is it likely to be any day in the next decade.

And what better case in point than a McKinsey study, undoubtedly written by some earnest 25 year olds who have no science background and have never been anywhere near a lab that does actual drug discovery work. This conflation of ligand discovery and drug discovery is perhaps the greatest public misperception of what the pharma industry does. I’ll partially forgive the McKinsey folks for probably not knowing any better. Less forgivable are the folks who have the scientific background to know better, but deliberately blur the line to those who don’t for profit.

More of the same. And if you know the origin of the meme, plays directly on the naïveté at work here.

Right now, there are too many AI in drug discovery practitioners who are hoping that the technology will advance quickly enough that the gap between what they’re promising and what they can deliver will close before anyone notices. But why do we have to take the hype train approach at all? Just tell me what it can do now without the BS. The inability to level with folks is not an endearing trait and makes me not want to do business with you. I don’t trade on FOMO.

Referencing my Substack in my Twitter in another Substack. Confused yet? Me too.

Take it from your future self: have fun now. Enjoy every second of your time in undergrad and grad school. There will be plenty of future days to work hard and have Serious Responsibilities.

Crap like this is just… I can’t. Cis and trans in organic chemistry are just descriptors, as they are for people. Not everything needs to be politicized.

This is all a long-ish way of saying that I wish there was more outreach from academia to industry. I wish every graduate program had regular career panels where folks from all walks of industrial life came in to talk about their careers. In the pharma industry in particular, it’s equally important to hear from folks in both big pharma and biotech. They’re very different environments, and I sense many universities pull on their big pharma connections only, if at all.

Most of our chemistry graduates are headed to industry, and the best way to understand what those careers are about is to hear from the source. (Better still is to do an industrial internship over a summer if your program will allow it.) My door is always open to participate in such panels. Hit me up if you’re an academic who needs someone for a career panel!

To be fair, I think this is less of a problem in chemistry than maybe it is in other fields. Regardless, nobody should ever be felt to made small or inferior because of their career choice. It’s a big tent and there’s plenty of paths for chemists to make useful contributions to society. Let’s value all of them.

I’ve thought so much about this particular dilemma, and I think I side with the 70% who chose the 4 day work week in person. Fridays off forever sounds wonderful. And there’s been so much dialogue about reducing the work week anyway. Some companies, admittedly mostly outside of the pharma sector, are already living the 4 day week. I expect a shorter work week to become increasingly normalized in the coming years. People are slowly but steadily redefining their relationship with work, and realizing they can still productively contribute something to society in less time.

We do like to eat around these parts, and particularly take advantage of the bountiful harvest of the sea that New England provides. Steaming up a few pounds of mussels is a fine way to have a quick and delicious weekend dinner. I also love the summer months when we can eat outside on our deck and enjoy the fresh air.

I catch myself backsliding into bitching occasionally; I think that’s just human nature. But I’ve tried to do it less. Building solutions is ultimately more rewarding anyway, even if it’s harder to do.

“Publish or perish” is not a big part of the industry mentality. “Patent or perish”, on the other hand, is existential in pharma. And it’s not the survival of your career at stake per se — it may be the survival of your entire company. Marketing exclusivity obtained through patenting composition of matter is central to the success of the pharma business model. I won’t place any judgment on that or try to delve much deeper into the subject as I’m not a patent attorney. But the need to patent is a key reason that peer-reviewed publications in the pharma sector are often many years delayed, if they ever come at all. It’s not that we don’t enjoy publishing our work; it’s that doing so prior to obtaining a patent runs the risk of invalidating a patent claim due to creation of “prior art”. It’s also a competitive business where many companies may be trying to drug the same target, and the last thing you want to do is give a lagging competitor a road map to how you succeeded.

I’ve said this so many times that we can start calling it Hornberger’s Axiom. Unfortunately, if it ever comes to pass, nobody (including me) will still be around to say “I told you so”.

The consensus seems to be that this was more of a tech sector phenomenon that a pharma sector one. The basic gist is that employers are stocking up on talent well beyond their needs, leaving scads of employees who are drawing a full salary while doing minimal work. While I’m a proponent of not watching the clock and just getting done what you need to get done, this seems like it’s going too far. It’s hard for me to imagine most scientists getting a great deal of satisfaction from working a small fraction of a normal work week. Maybe I’m wrong though; attitudes toward work and work-life balance have certainly changed a lot since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.