Ramblings: June 2024

7 August 2024

Below are collected Twitter ramblings for June 2024. Apologies I’m a little late dashing this one off. I’ve been traveling a lot in July — going to a GRC, some vacation time at the beach, and visiting family — so writing time has been sparse. I also usually send these out on the weekend, but since I’m stuck in a pressurized metal tube at 32,000 feet today, it’s a good time to catch up on writing! Without further ado…

This month’s photo of the month is from Giuffrida Park in Meriden, CT. This walk along the ridgeline on the Mattabesett Trail offers exceptional views of the Hubbard Reservoir; the Hanging Hills are also visible off in the distance.

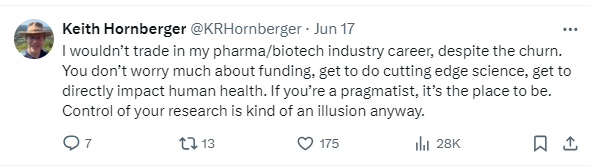

This is one of those things that’s a stark reminder of how things aren’t always sunshine and roses in industry. Yes, the pay and benefits are generally better in industry, and if you’re oriented toward solving real-world problems, it’s the best place to be. But the sometimes-ugly flip side is that you are, indeed, working for a business. Which means there are always associated economics. Pharma and biotech companies ultimately exist for the same reason as any other business in a capitalist economy: to make a profit for their shareholders. Strategic realignments, headcount reductions, and site closures can happen at any time and for a host of reasons. Often, those reasons are disconnected from the performance of an individual, group, or department. It can be as simple as the company wanting to consolidate two physical locations into one to save money, or deciding to exit a therapeutic area after a prolonged losing streak in that area. (Anyone who’s worked in neuroscience in big pharma can undoubtedly tell you about the latter.)

Although it would be great if companies were a little more nuanced in how they do such things, it just doesn’t shake out that way a lot of the time. This can lead to high performers being impacted despite their high performance, and it’s why I encourage everyone to keep their CV current and be ready for the worst at any time. All those excuses in your head about why it won’t happen to you are just that — excuses.

There’s a deep truth in this statement that grows more profound the more you think about it. Anytime you find yourself saying, “I don’t have time to do X,” there’s an implication in there that X is important to you but you can’t fit it into your life. Rather than hand-wringing, this is an invitation to consider how you’re spending your time. If X is really that important to you, then figure out what you’re doing that’s less important, and stop doing it. Not everything you could potentially spend time on is above the payline. A little active management of your time will go a long way toward suppressing those feelings of FOMO. When I was younger and didn’t have kids, I spent more of my weekends playing video games. I still love video games, and when new stuff comes out, I sometimes get those pangs and wish that I had more playing time. But then I remember I’d much rather spend that time with my kids, or hiking, or writing this blog — and any regrets subside.

I got another blast of this driving to the airport at 5:45 am today. There are so many people who are morning people out jetting around at this hour, but I’m not one of them. At work, I’m never going to be one of those people who springs out of bed and starts answering emails at 5 am before squeezing in 45 min on the treadmill and then hopping onto my first call at 7:30. For one thing, most of the year I have three kids to help get out the door before I can even worry about myself. For another, I’d just rather have that bit of extra sleep in the morning. Most days I get to work at 9 — occasionally 8 if we have a call to one of our CROs overseas due to the time difference. But I also get a big burst of energy in the late afternoon. My most productive hours are 4-6 pm — and sometimes I don’t mind staying past 5 if I’m in a groove and want to keep going. There’s no one right way to approach your working hours, so do what works for you.

This mindset of “failing is failure and succeeding is just doing your job” begins in grad school, or even earlier, for many folks — and sometimes it never goes away. This is madness in a line of work where 90-95% failure is the expected baseline. There’s no room in that mindset for recognizing and rewarding a job well done, despite the ample evidence that high ratios of praise-to-criticism lead to more productive teams. Take a minute out of your day here and there to thank a colleague for their work. It’s all upside to do so.

Regular readers are aware of my longstanding crusade against all adverbs, and above all “importantly,” in the scientific literature. Adverbs add so little to a manuscript, other than editorializing. “Importantly” almost always translates as “importantly according to us” — and also doesn’t give readers any credit for their own ability to figure out what’s important in a paper. If a paper is so muddled that you need to use words like “importantly” to call out the important things, maybe that’s a wake-up call to spend a little more effort cleaning up your writing. A golden rule of scientific writing is: if removing a word or phrase doesn’t change the meaning of a sentence, then remove it.

Just my $0.02, but this is not a great way to make decisions that impact your entire company. There are lots of new tools out there that could make your work life better, but rather than get stars in your eyes — which often stems from a lack of expertise with the tools in question — maybe a more measured approach where you engage trusted experts for a balanced opinion is warranted. In the drug discovery arena, generative AI isthe latest in a long line of shiny objects that will have their uses, but are rarely going to warrant insane levels of investment based on the “mind blown” experience of an individual. Being a leader and setting a strategic direction doesn’t mean chasing FOMO — quite the opposite.

I’m with the 74.3% on this one. mL/min/kg units put most clearances in most species in the range of 0-100, which are comfy numbers for our brains. L/h/kg units are frequently fractional, and — to my mind — annoying to look at. There’s no one right way, of course, but like most things, these patterns get set inside a company by the prior experiences of the individuals doing the work. And “because we’ve always done it that way” is not usually a good reason to do anything.

While I can’t say I have fond memories of my days working with Lawesson’s reagent (many days, I fought the Law and the Law won), this chemistry had a key place in the discovery of dabrafenib. Systematic survey of the core thiazole 2-substitution required making a large series of thioamides and thioureas, most of which were done in my lab. We owe the t-Bu substitution in dabrafenib to that chemistry.

You know the kinds of paper I’m talking about. Maybe the statistics are improperly done. Then the IC50s are reported to two decimal places. Then a graph is on a linear scale when it should be logarithmic for proper interpretation. Then you look a little closer, and a few more things are just… ever-so-slightly off. It all kinda-sorta hangs together, but you wonder if the people who did the work really knew what they were doing.

There’s plenty of room for different labs to do similar experiments and reach similar conclusions. Indeed, this is a great sign that the findings are real, because there’s a level of reproducibility. But in the above case, the second paper clearly had full knowledge of the first paper. At what point does it stop being an independent finding?

I started Twitter posting largely based on this philosophy, and it’s worked out well. I’m still sometimes amazed how many people have come along for the ride.

There’s a right place for every scientist, and industry is mine. It’s also a simple reality, at least in chemistry, that there are more industry jobs than academic ones, so most of us are going to land there in the long run. It has its good things and bad things — the lead-off to this month’s blog hit on one of the biggest bad ones of them all. But the big good one is the opportunity to improve human health. That’s why I get up and go to work in the morning.

There’s probably a #VPLife hashtag waiting to be born here. I can’t describe in a few sentences all the ways in which my job has changed since I became VP of my department. But oh lord, some days there are a lot of meetings and people vying for my time. So many of the things are worth time too, but there are only so many hours to give in a day. Prioritization of what’s most important is a work in progress. There have been some times where I haven’t gotten it right and went to the wrong meeting or should have delegated a task to someone. I’m slowly fine-tuning my sense of how to spend my time to provide the most benefit to the folks in the department.

Shaming has no place in a work environment. It’s straight-up toxic behavior and will demoralize everyone. It goes way beyond an individual who was shamed, because others in a group will see what happened to that person and adjust their own behavior accordingly. Both by being more guarded in what they say, and in the worst extreme, by becoming shamers themselves — because they’ve learned from those above them that it’s okay. It’s far better to go down the path of admitting what you don’t know and lifting up those who may know more than you do about a given topic. That’s the way to have everyone learn and realize their full potential.

There are only a handful of real regrets that I’ve carried with me through my adult life without letting go, and perhaps strangely, this is one of them. If Columbia would ever let my 48-year-old self come back for commencement someday, I’d happily walk with people half my age with my head high.

There are always conversations at Nobel Prize time about the “fourth person” who will be left out of a prize in a given year, because the limit is three people. In 2010, the year that Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling finally got its due, those three people were Heck, Suzuki, and Negishi. Speaking as both a synthetic organic and medicinal chemist, this was a richly-deserved prize. But sometimes the UA 232 story pops into my consciousness, and there’s no doubt in my mind that Stille would have been in the mix in 2010 if he was still alive.

The latest FDA Modernization Act has opened the door for the agency to accept an IND without animal testing, but most folks seem to agree that this “modernization” has gotten ahead of reality on the ground. So far, neither the agency nor the pharma industry have demonstrated much desire to test those waters. I’ve heard, though — most recently at the Drug Metabolism GRC — that there are a few entrants lining up to try. So until that better future comes along, it will remain true that most drugs tested in animals will fail in people — because all drug candidates are tested in animals (until recently, by law), and most drug candidates fail in the clinic, or before.

And y’all wonder why I post cocktail recipes.