Ramblings: May 2023

1 June 2023

Below are collected Twitter ramblings for May 2023, with the usual color commentary interspersed.

This month’s photo of the month is of Day Pond Brook Falls in Salmon River State Forest in Colchester, CT. The falls were relatively high due to a good deal of early spring rain, and in spite of an almost nonexistent spring melt after a mild winter.

I’ve seen feedback from frustrated job searchers on Twitter that their résumé or CV doesn’t even make it out of the initial triage for a phone interview. Sometimes this can be down to a true lack of skills requisite for the job. But in other cases, it may be that whoever is reviewing the CV — be that the hiring manager, an HR representative, or yes, some AI algorithm (which I’m sure happens some places) — can’t see that you have the skills because you didn’t emphasize them. This is why it’s so important to read the job description and custom tailor your CV to it. No, you cannot just throw the same CV into an electronic pile for 10 different jobs and expect good results. By reading the job description, you will see what matters to the individual employers, and you can pull out the right keywords to attract interest from the recruiter(s). If a job description says “proficient in organic chemistry characterization techniques such as LC/MS, 1H NMR, etc.” your CV should include LC/MS and 1H NMR in your list of proficiencies (assuming you have them).

I’m so glad I went to this ACS Connecticut Valley Section symposium. Not only did I get to see my colleague Dr. Dana Klug speak about PROTACs, but I also got to see the latest from Christina Woo and Dan Nomura, and a great lineup of student speakers. Inevitably, most medicinal chemists develop some rust in their synthetic skills, and these talks were a good shot in the arm for that.

Well, of course the biggest perk of going to that symposium was that I finally got to meet Twitter’s own BagPhos (aka Scott Bagley) in person. I hope I’ll get to meet more Twitter friends in person in the future.

A simple message but one that seemed to resonate. Skills I took with me that were valuable to my employers: organic synthesis design and laboratory techniques, literature searching, purification techniques, analytical methods for characterizing compounds, persistence to crack tough problems and find work-arounds. All of those things are useful to the budding medicinal chemist. My total synthesis of (+)-killotsapeoplone specifically? Not so much.

Got such a lively bunch of responses to this question that ran the gamut from “I’m doing exactly the same thing today” to (mostly) “I learned some general useful skills but am doing something tangentially (or radically) different day-to-day”. I retweeted all of them for visibility. I think it’s important for folks to see that they aren’t defined by the details of the work they’re doing now, and there are lots of ways to port their current skills into something else.

This is when I learned hard and fast that AI tools like Midjourney are not well-suited to the concrete specifics that a scientist needs. Infographics are completely beyond it, even when I spoon fed it the exact information that should appear in the graphic. A tool like Midjourney could be really amazing for presentation graphics if the darn thing learns how to take specific instructions rather than just abstract everything. But if I ask it to render a low sunset off the coast of Hawaii while two people sit on the beach sipping tiki drinks, it will knock that out of the park. (Some possible projection to a future vacation there.)

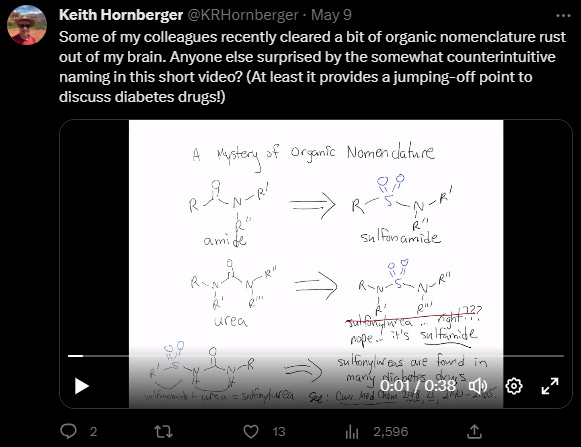

I have a few ideas in mind for future sketches in Procreate to illustrate, in particular, certain concepts in pharmacokinetics. This whole sulfonylurea/sulfamide nomenclature thing still rankles me a bit though.

If you’re like me, your feed is getting overrun by hucksters writing power threads on how to use generative AI to do your job for you. Pro tip: tapping the three dots next to any tweet and then “Not interested in this Tweet” consistently will gradually reduce the amount of this crap in your feed.

Summers are fleeting in New England, and given that I have flexibility to work from home several days a week, I like to work outside when I can. Just that small bit of remove to the outdoors does wonders for my attitude throughout the day. We have a deck, a patio table with a large umbrella, exterior electrical outlets to plug all my devices in, etc. With a smidge of work I can easily set up a second monitor and basically completely mimic my home office setup outdoors. I’ve even had a couple of colleagues on meetings see my video and be like, “Wow, you’re outside again?!” To which my response is, “Why aren’t you outside more?”

I also posted this on Facebook and one of our local friends who raises chickens told us that she gets wolf spiders in her chicken coops all the time. To the point that she keeps a putty knife on hand to whack them in half and then lets the chickens do the rest of the work. 🤢

You can also learn a lot about how people drive by observing how they steer their cart in the supermarket.

I’ve often said that new PhDs coming to medicinal chemistry in the pharma industry are basically embarking on getting another PhD. After 20 years, the accumulated experiences of a talented MS chemist in pharma often make them just as skilled, if not more so, than a newly-minted PhD. Stories of folks moving up through the ranks to the PhD level are still relatively uncommon, but when you find one of those folks in your group with the talent, grab them and hold on tight.

As I’ve gotten a little older, helped raise some kids, and moved a little further up the food chain at work, I’ve learned this thing to be true. It’s easy early in your career to be focused on yourself and your own learning and growth and advancement, and sometimes you get so focused on those things that you begin to view them as adversarial with others. That’s wrong. True fulfillment comes, in the end, from being able to pass on what you to know to others and enabling their success. It’s one of the reasons I’ve chosen to be more active on Twitter for the last few years.

All. The. Time. I’ve written elsewhere about the hallmarks of bad pharmacology in publications, but sometimes they’re cleverly hidden. My general approach to reading most manuscripts is to not read the whole thing. (Peer review being an obvious exception; there you have to read everything closely.) There was a time up until a few years ago when I did read everything start to finish, but those days are past. I’ve learned that I can cover a lot more ground at the right level of detail by being more selective. For a new paper, I’ll generally read the intro and the discussion/conclusion sections. If bold claims are made or it’s particularly relevant/interesting, then I’ll review the figures. Only rarely do I read the whole body text after that. Usually the figures provide the first flags of bad pharmacology: high drug concentrations, effects in various assays with misaligned concentrations, etc.

Although I’ve written my fair share of words about the differences between industry and academia, one should not be left with the impression that one is intrinsically better than the other. They’re just different. Yes, I understand the allure of competitive pay, benefits, working hours, etc. that come with an industry job. Also coming with that job are: reduced freedom to work on exactly what you want to, nth degree bureaucracy (especially in large pharma; less so in biotech), real and sometimes immutable deadlines (especially in development), and occasional soul-crushing layoffs. I’ve worked four different jobs in 21 years and, at last count, my family and I have done three really big house moves and lived in nine different places, including stints in temporary housing. The days of stability and working one job in pharma for your whole career are largely at an end. You’ll still find 30 year veterans who’ve managed to stay in one place the whole time. They are the exception.

Lumping these two together. AI in drug discovery has become a favorite punching bag of mine over the last year or two, and not because AI models have nothing to add to drug discovery. I fully expect AI to contribute meaningfully to drug discovery in the future — as a tool in the toolbox, alongside all the other tools. Right now, it has high potential for use in ligand discovery, where there’s a little less noise that needs to be cut through. Unfortunately, ligand discovery is not generally the rate-limiting step in drug discovery. Clinical trials are, where the overall failure rate hovers around ~95%. And that’s precisely the place where the real world data contains so much noise that AI will struggle with the “garbage in, garbage out” problem. My objection, then, is to the endless parade (unholy alliance?) of drug discovery veterans (who really ought to know better) and Silicon Valley tech bros (who are on the peak of Mt. Stupid on their own Dunning-Kruger curve) who are hyping AI technology as the cure for all our ills. In short: embrace the technology where it will help, but beware the oversell.

Vide supra.

The single biggest leading indicator of unreliable pharmacology is the need to dose to high (micromolar) drug concentrations to see a mechanistic or functional effect. It’s not that such studies are intrinsically wrong, just that the probability of polypharmacology goes up considerably as drug concentration goes up. No drug is perfectly selective and it will start hitting off-targets at a high enough concentration. If the potency against the primary target is already in that high concentration range, watch out. Ask any toxicologist who’s ever run a tox study. They deliberately dose drugs at exposure multiples well past the expected efficacious exposure because they want to see where the limits are. They’re usually not happy unless they see some signs of toxicity.