Ramblings: May 2024

23 June 2024

Below are collected Twitter ramblings for the month of May, expanded and elaborated in the usual way.

This month’s photo of the month is from the River Road Preserve in Roxbury, CT. May is the month that spring finally springs in Connecticut. Trees are leafed out, flowers are in bloom, and the rivers are running a little above normal after a rainy couple of months.

Longtime readers and friends know that I grew up in Maryland, just a handful of miles south of this new, yawning gap in the local infrastructure. I crossed the Francis Scott Key Bridge hundreds of times in my youth. In truth: it was not a great bridge. It had narrow lanes, no shoulders, and short barriers on the center span separating you from a plunge into the Patapsco River. It was a white-knuckle drive for 16-year-old me newly armed with a driver’s license and visiting my grandparents on the east side of Baltimore. But also truth: it served a purpose, connecting communities and providing a hazmat route around the city (hazmats not being allowed in the two harbor tunnels). As I write this, a big chunk of the cleanup is done, and the years-long task of building a new bridge remains. I hope the state and federal governments seize this opportunity to build an iconic span for the city.

Although I’ve long since converted to reading papers electronically (big ReadCube fan here), I’ll probably never kick the habit of editorial comments in the margins. Sometimes they’re the most useful reminders of the gist of a paper when I have occasion to look back over something months or years later. For every 4-5 JFCs, though, there’s an equally important “!!!” on something remarkable. How do you annotate your reading stack, readers?

While there’s a grain of truth to “good artists copy, great artists steal”… in this case it was outright plagiarism by a conference organizer, and that sits poorly with me. Dennis has worked hard over the years to build up Drug Hunter as his business, and it’s not okay for someone else to just take his stuff without asking. While no law was broken, content creators do have a reasonable right to some attribution. You don’t have to attribute, of course. But you also have a choice to not be an asshole about it. Don’t be surprised when other content creators don’t want to work with you anymore, lest you do the same thing to them.

It’s hard to see this new ad from Apple as anything other than a frontal assault on human creativity. I know they were trying to make a point about “look at all this cool creative stuff we can cram into a tablet”… but it came across as crushing the soul, and social media responded accordingly. Here and in drug discovery, we are a long, long way away from taking humans out of the loop. The best medicinal chemists are creatives in the same sense as musicians and other artists, albeit with a scientific foundation. I saw several folks make a version of this ad with the video run in reverse that conveyed the same message without the sad feels.

I’ve now sat through 22 years’ worth of PowerPoint slide decks in the pharma/biotech industry. I’ve seen some great ones, and also some epic fails. The lowest common denominator of the fails: they ramble. Know who your audience is, and tailor the message accordingly. The level of detail you’d use when talking within a project team is inappropriate when delivering a strategic message to management. I encourage teams to come in armed with an appendix of details so that if someone really wants to get into the minutiae you’re prepared — but most of the time you’ll never need it. Good management teams in drug discovery place a high degree of trust in project leaders to be on top of things, and don’t feel the need to rummage around in the details. Most of the time, a management team wants to know: do you have all the resources you need? are there obstacles in your way that we can help to clear? are you keeping to your timelines? etc.

AlphaFold is often held up as a triumph of AI in drug discovery, and to be sure, AlphaFold can do some pretty cool stuff. But what’s rarely acknowledged by the more hype-prone AI advocates, who want to extrapolate what AlphaFold can do to all corners of drug discovery, is that AlphaFold has trained on a champion data set. The scientific community has been dutifully gathering and depositing protein structures into the PDB for a very long time, and AlphaFold can work its magic precisely because of that trove of data. There is no other data set in biology that even comes close to what the PDB provided to AlphaFold. Which is why I caution people to ask the question “What is the training set?” anytime an AI proponent approaches you with a model. Quite often, the emperor has no clothes.

And case-in-point right here. Although one should take the referenced review with a grain of salt because it was done by a consulting firm, when you take a close look at just what AI is “discovering” in drug discovery these days — targets and ligands alike — it’s not exactly traveling into uncharted waters. How could it? Consider what it was trained on!

The larger point about clinical success rates, well: it’s just way too early to say what, if any, impact AI tools will have. The sample size is small, and there’s no reason a priori to believe that AI-derived clinical candidates against AI-derived targets will somehow come out smelling better in the clinic. Why would they? The models have largely not been trained on and optimized to solve the clinical failure problem, so it’s reasonable to hypothesize that they’re going to get mowed down at the same rate as the clinical candidates discovered by humans.

To the point that you can make a meme out of it.

More than one meme, in fact.

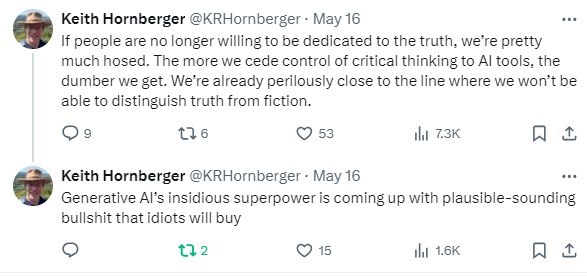

Anyone who’s tried to use ChatGPT or its ilk to address even relatively basic questions in chemistry or drug discovery can tell you that you can get both reasonably correct (but often subtly wrong) answers as well as things that are purely hallucinated — but sound quite believable, especially to a non-expert. Imagine a future where there are no more experts because we’ve handed over the steering wheel to our AI tools. How will we be able to distinguish reality from hallucination?

Say nothing of the fact that this inability to distinguish has already spilled over — approaching apocalyptically — into our civic life. I have little hope that AI is going to be some great uniter and instead fear it will push us into further polarization. AI is giving a huge chunk of humans a pass to give up on critical thinking and deducing for ourselves what’s truth. It’s just human nature to derive greater comfort from what we want to be true than by confronting what’s actually true.

There are a lot of factors that go into the “why do drugs cost what they do?” question. The whole mess of insurance companies, pharmacy benefit managers, government price controls, and on and on all have their role to play. But a fundamental one that is directly in the hands of the pharma sector that’s inescapable is: we fail in the clinic. A lot. 90-95% of drug candidates fail in the clinic. And you still have to pay the development costs for the 19 that failed to get you to the one that made it. And all of those development costs — failed and successful — have to be rolled into the pricing of the ones that make it in order to run a profitable business.

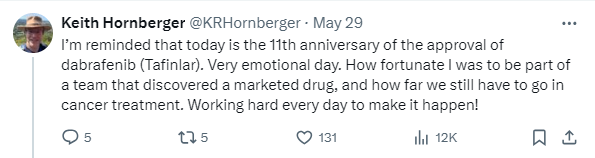

Aside from the pricing discussion, this failure rate also has a big bearing on this factoid: most drug discovery scientists will go their entire careers and never work on a team that discovers a marketed drug. Back-of-envelope, a discovery scientist might spend 5-7 years working on a single project if it goes all the way through from early discovery to clinical candidate nomination. So — best case — you might get to participate directly in 6-7 such efforts in the span of a career before you retire. Given that 19 out of 20 clinical candidates aren’t going to make it, it’s then clear why most of us will hang up our spurs without a drug to our names. And also why the single most important question a discovery scientist can ask themself is: what target should I be spending my time on?

The number of papers that continue to get published on curcumin analogs is just staggering. To the point that some years ago there was a whole review dedicated to the fact that pursuing curcumin and its relatives is a Bad Idea Indeed. If you’re gonna go there, okay — but go in knowing that the burden of proof is on you, and it’s a high hurdle to clear. Peer reviewers and editors on these manuscripts need to do a better job holding feet to the fire.

There’s a list of functional groups that are known to either be reactive in their own right or produce reactive metabolites. I’ve written in the past about some of these nuisance groups such as nitroaromatics, quinones, phenols (which are waiting to be quinones), and the like. Michael acceptors (and even unactivated alkenes, which are waiting to be reactive epoxides) are another. When I see any of these functional groups in a compound that’s the centerpiece of a manuscript and the authors don’t even acknowledge their presence, let alone do a single control experiment to rule out confounding mechanism(s) of action… folks, you just have to put those papers down and move on to the next one. I suspect most of the time it just comes from ignorance, but that doesn’t make the conclusions in such papers any more sound. This is another area where editors and reviewers need to do a better job being the firewall and demanding proper control experiments. Most of these papers would never make it to publication if the right controls were done.

Like any new technology, AI will go through its hype cycle. As some of that balloon bursts, jobs are inevitably going to be lost. But the point is: every new technology goes through a hype cycle and will experience these ups and downs. And that’s entirely apart from any larger macroeconomics affecting the entire pharma/biotech sector, and there have been quite a few headwinds in the last few years. Lots of pharma companies are laying people off right now, not just AI companies. So do what you can to support anyone going through layoffs. You’d certainly want folks to be there for you if it was your job that got axed.

Honestly, I was pretty happy in my old role leading the oncology chemistry group, and for quite a while actively dismissed the notion of being VP one day whenever the subject came up. I’ve been at my current company for a long time and watched it grow from less than 40 people to over 400. Being VP would be a chance to leave a stamp, but with a long track record, I felt I’d already left my imprint on the research organization.

Sometime in the last year, though, I changed my mind on this and decided I did want the job someday. A big driver was the realization that I wasn’t learning as much as I used to in my current role, which tends to happen when you’ve been doing the same thing for a while. You get good at it, and then — maybe not bored, but in search of new challenges to learn from. So when my boss decided to retire — here we are. Fingers crossed I don’t mess it up!

The takeaway here is that it’s worth spending time every year on career self-reflection, because you might change your mind vs. what you thought a year ago. I’ve written some questions to guide this thinking, and have tried hard over the years to practice what I preach.

You can read the thread for all the pharmacological missteps that were made in this particular paper. What I want to address here is why I don’t name and shame such papers. We should question: what’s the motivation for naming names? Sure, it would probably feel good to call these papers out and would make a glaring example for all to see with flashing lights. It would make me feel better and I’m sure there are plenty of people waiting to pile on who would revel in doing so. But it would not make the authors feel better. It’s called “name and shame” for a reason. Not something I would want done to me, and so I will not do it to anyone else. Getting grumpy on what had already been a rough day, as in the thread above, is about as far as I’m ever going to go.

I think one of the worst things you can do when trying to educate is to make someone feel shame because they did something wrong and probably didn’t know any better. My goal is to educate folks on how to do things better, and you can do that in a (relatively) constructive — and anonymous — way. I would rather be a teacher than judge, jury, and executioner on every crappy paper I’ve read.

As I’m writing this, I’m reflecting on one my earlier comments in this post about how most drug discovery scientists will go their entire careers without being on a team that discovers a drug. I was exceptionally fortunate to be on such a team, and within the first 6 years of my career at that. Will lightning strike twice before I hang it up? If I knew what the magic formula was, I’d bottle it up and sell it. But I do know, now more acutely than ever in middle age, that you only have so much time on this earth to leave good works behind. So make the most of it. Choose wisely.

Just get to work. All the talk in the world won’t get a drug candidate through clinical trials to patients. I want to spend my time with people who are willing to dream big dreams, and then get down to the business of making them real.