Below are collected Twitter ramblings for October 2023, with the usual color commentary.

This month’s photo of the month is taken from the summit of East Rock in New Haven, CT. Downtown New Haven is visible off in the distance, and on the left is Long Island Sound.

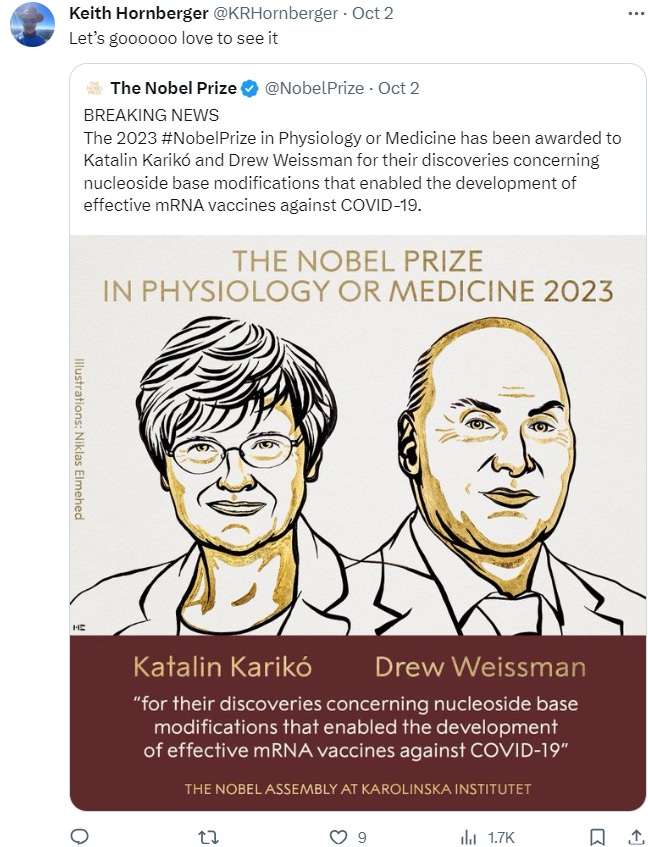

There’s an old bit from Hemingway in The Sun Also Rises when one of his characters went bankrupt, was asked how, and he replied, “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” That’s the story of this Nobel. Katalin Karikó toiled for years — decades — in obscurity working on mRNA. When the breakthrough finally came, it was under-appreciated at the time. And then suddenly the COVID-19 pandemic burst onto the scene, mRNA vaccines got real in a big damn hurry, and here’s the result 3 years later. Couldn’t be happier. Except maybe if there had been a co-Nobel in chemistry for the lipid nanoparticle formulations that make the mRNA vaccines work.

Not surprised this is the line that Penn took, but disappointed just the same. They took a full body blow from Community Notes though — I think this functionality is quietly one of X/Twitter’s best features. Karikó has made her peace with Penn apparently, showing up at press events, etc. after the Nobel announcement. I’m glad she turned the other cheek, but not sure I would’ve been able to do the same.

This is the third year I’ve done this post, and the comments are a great way to get the temperature of the chemistry community. This year ran the gamut from vaccine deniers to the hexacyclinol crew to cold fusion. Worth a read-through if you need a snicker.

The ratio of things I’m asked to peer review vs. the number of things I’ve submitted for peer review is… a large number. Like many folks in industry, I don’t publish all that often. Medicinal chemists generate the core intellectual property that makes the pharmaceutical industry go. Patenting our work is the first order of business. If we get to tell our stories — and it is an if, not a when — often many years have elapsed since the work was done. We get “scooped” by academics who did similar things to us many years after we did them (and patented them) all the time. In the end, publications aren’t why we do what we do, and our work can have far-reaching real world impact without there ever being a publication. We do still like to publish when we can, but there are many more barriers to doing so.

If you find your work day increasingly consumed by meetings and process, it’s worth thinking about this old Reed Hastings principle. Larger organizations tend to be more complex, and with a decreasing talent density. This complexity is a primary driver for process and bureaucracy, but the root cause is insufficient talent driving a lack of trust from above. The solution is: increase the talent level in your organization, including letting lower performers go if you must. Then set your high performers free to go do their jobs with only loose coupling and oversight from above. In pharma, no manager or C suite person can know the project science and drive to a clinical candidate better than the project leaders can. So get out of their way. In fact, the best thing senior leaders can do is to clear obstacles from the team’s path so that they can execute.

Don’t just go on “this position requires 5-10 years of pharma experience” — often those metrics are surrogates for the amount of time perceived to be needed to absorb the necessary skills to do the job. Really read the job description before you apply for something. Make sure your CV/resume describes how you can do the core competencies listed, or at least could grow into them based on the competencies you have today — and worry less about the number of years. In times when the labor market is tight, such as what we just went through in 2020-2022, these experience metrics are often aspirational.

This principle was first brought to my attention by David Epstein, who was SVP of the drug discovery organization when I was at OSI Pharmaceuticals. At the time he said it (in a town hall meeting, I think), I didn’t really grasp what he was getting at. I was just the chemist. But time wore on, and I found myself thinking about this idea more and more. In the end, pharmacology really is the glue that holds the pharma enterprise together, and we all do need to know some of it.

This behavior, however necessary, will not win you any friends at a big pharma, where processes and procedures have long since ossified into a state of near-permanent inflexibility. Change can happen there, but it’s slow, and often governed by its own set of change management processes. You have a better chance to rock the boat at a biotech, where culture is what you make of it. The tradeoff there is that biotech can be a bit like the Wild West until someone defines the cultural norms — so if you need order and structure everyday, it’s maybe not the best fit. This is something important to consider when thinking about what kind of environment you want to work in. I probably just tipped my hand about where I fit in best.

Jaws is such an eminently quotable movie. Robert Shaw’s monologue about the sinking of the Indianapolis is one of my favorite movie moments of all time.

Oh man, this is really the crux of the whole thing. The pharma sector is oft accused of unimaginable greed, but when you bring that down to the level of the individual scientist, it just doesn’t wash. I don’t know a scientist in the industry who went into it for the money. Sure, it may pay better than the average academic job. But if a smart person wanted to be rich, I can think of a half dozen other lines of work I’d go into before I did drug discovery. Most of us do this to leave an impact on human health, often for deeply personal reasons, despite the absurdly long odds.

Faking data and duplicating lanes on western blots is one thing, and that’s bad enough. Making up an x-ray crystal structure is a whole other level of crazy. A hard line needs to be taken here to protect the integrity of CCDC. And remember, this is the training set for AlphaFold — has anyone thought through the ramifications of fake training data?

The clinical failure of AI-discovered (being generous here using “discovered”) drug candidates was, to anyone who’s been in the industry long enough, inevitable. AI is making an impact on ligand discovery, which — as I and many others have said — is not the same as drug discovery. The reality is: from the time a clinical candidate is nominated — meaning the moment that my colleagues and I in discovery have put forward the best molecule that we can to the very best of our collective ability — the failure rate in from clinic to launch is 90-95%. This is the true rate limiting step in drug discovery, and I have seen very little evidence that AI can impact the clinic. It’s noisy data for one, and the failure rate is also indicative of our poor understanding of disease biology. Most things these days are washing out for lack of efficacy. I have yet to see the AI model that can predict that well — and this is precisely the area that needs work if one really wants to revolutionize the industry. “More shots on goal” is meaningless in terms of capital burned if we just continue to have clinical failure at the current rate.

Project leaders are the owners of the deliverables for the project, ultimately including the nomination of a clinical candidate. Things can and will fall out along the way because science can be a real bitch. So I tell project leaders: you’re not going to be taken to task if the project reaches a data-driven no-go decision. That happens; it’s the way science works. But you are held accountable for the execution of the project. How you get to that decision is within your control, and matters.

LinkedIn does have its uses, but it’s the most sterile form of professional communication we have. I strongly prefer Twitter, because people are more real and unvarnished there. I have little patience for corporate speak online. There’s enough of that in most folks’ day jobs as it is.

So important to learn this presentation style in industry! Imagine every presentation you have to give is going to be truncated to 5-10 min — which happens sometimes. Given this reality, what do you want to convey in those 5-10 min? It better be the bottom line of your most important results and what you need to keep moving things forward. Everything else is details that you can fill in if time permits. Focus — ruthlessly.

This gets to the heart of the difference in the way medicinal chemists and process chemists approach synthetic routes. In a discovery environment, we’re seeking a potential clinical candidate molecule. While doing this, we know that 999 out of 1000 molecules (not an unrealistic number of compounds for a lead optimization campaign) will not be the clinical candidate. Therefore, synthetic route investment has to be scaled accordingly. It doesn’t make sense to make a gram of everything in 90% overall yield, nor to invest the time in route development to make that the case, when almost everything you make is going to wash out for one reason or another. Furthermore, medicinal chemists design routes to introduce structural diversity as close to the end of the route as possible — so that we can get to an initial read on those 1000 molecules more quickly. We’ll do it this way even if the overall yield would be better introducing diversity early in the sequence, because the time saved by reducing the number of synthetic operations — even at the expense of considerable amounts of yield — is worth it. Get answers on the majority of compounds — which will fail — first, and then focus on route optimization for the few that survive later. This is the way.

More simply: don’t over-engineer your molecules. Answer questions and move on.

I wouldn’t have even gone to graduate school except for the fact that I had a professor in my sophomore year of undergrad who told us that grad school was free. (“Free” does have important riders though, such as the 5 years working your ass off — but I digress.) I had no idea! Going someplace like Columbia would have been way beyond my financial means without a tuition waiver and stipend. Which is why I always tell people: dream a big dream in your grad school applications. Apply to lots of schools, and go to the very best one you can get into that has multiple faculty you’d be thrilled to work for. And unless (although maybe especially because) you have strong ties to a specific place, this is the time in your life to go live somewhere else for a while and have a big adventure! It will be easier now than at any subsequent point in your life.

These two go together. I had a delightful time speaking with Laura Howes while she was putting this piece together, and we talked about quite a large number of topics off the record. I was insistent though that we consider this a “new age” rather than a “golden age” of drug discovery. The original golden age predates my time in drug discovery, and indeed that of most current practitioners. What we have seen though of late is that new modalities previously considered a little crazy — such as targeted protein degradation, or more broadly proximity induction — are turning out to be practical. Rumors of small molecule demise always seem to be exaggerated. We spent a solid decade (possibly more as it’s still going on in some quarters) going gaga for biologics and commiserating on the decline of small molecules. But remember my Drug Discovery Axiom #1: there are no panaceas in drug discovery, only tools in the toolbox. When I’m feeling a little pithy, I remind folks that antibodies work great for all targets, unless they’re in the cytoplasm or nucleus.

I guess we have to consider this a friendly pumpkin rather than a scary one. Who doesn’t like a good pumpkin π?