Ah, structural alerts. Several different implementations of that term are sure to get your average medicinal chemist riled up. On the one side, we’re sick and tired of watching the medicinal chemistry literature be polluted with garbage. The knowledge that certain functional groups can lead to some toxic, mutagenic, or carcinogenic outcome in a great many cases is sure to trigger us when someone who is oblivious blindly publishes a structure containing one of these groups in the latest J. Med. Chem. That’s a severe breakdown in the peer review and editorial process, which I could go on about at considerable length. It’s not that these structures are Always Bad — more on that in a moment. No, what gets us going is the sheer ignorance of the fact that some of these groups might actually pose a problem in the first place. That awareness would then set off follow-up experimentation, which would remove a great deal of bad publications, and attendant conclusions about some target pharmacology, from the literature before they ever even got off the ground.

On the other side, well… these functional groups are often a problem, yes. But often is not always. Anytime someone pops up a “rule” around structural alerts, you can bet your bottom dollar there will be an agitated and pedantic medicinal chemist somewhere out there who will delight in breaking it, and then telling you why you’re wrong. These kinds of things can become institutionalized in drug discovery, to the point that companies are pre-screening molecules for structural alerts prior to registration — or even during ideation — and then tossing those molecules out as not worth pursuing. That would be an entirely opposite — but equally wrong — kind of not thinking about the problem. If you’re a blind rule follower, seek a different line of work than drug discovery.

As with many things in medicinal chemistry, an appropriate balance is key. First, be aware that certain functional groups can be frequently problematic. Second, if a particular SAR (or screening hit) leads you to a molecule that contains one of those functional groups, that’s fine to pursue — but it comes with the understanding that there are risks, and that you carry the burden to experimentally discharge those risks if such a molecule continues to progress through the screening cascade. It’s probably worth discharging that risk sooner vs. later too, lest you spend too much time barking up the wrong tree.

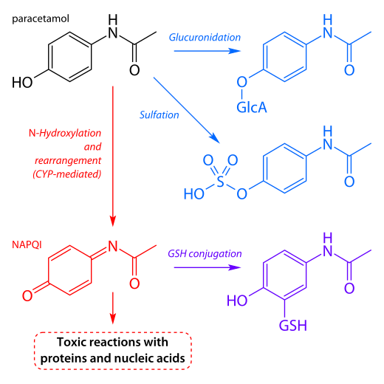

Without further ado, here comes part one, focused on the notorious redox cyclers. Nitro groups and quinones come into focus here. But also some key points about how many structures contain latent quinones that are one or two metabolic steps removed from the quinone, and you wind up at the quinone in vivo anyway. Stay sharp!